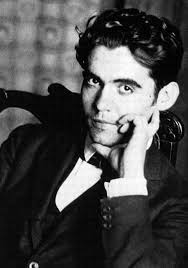

Federico del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús García Lorca 05/06/1898 – 19/08/1936

Federico García Lorca, born in June 1898 in the small town of Fuente Vaqueros (near Granada) is a universally known poet and writer. But just as he is recognised for his literary achievements, his name is also well known for what happened on 19 August 1936.

García Lorca grew up with his father, Federico García Rodríguez, a successful farmer, and his mother, teacher Vicenta Lorca Romero, on their farm until moving to Granada in 1909. Six years later he started at the University of Granada, and despite being a gifted musician, he started writing. Just one year later, García Lorca travelled through Spain, and self-published his first book, Impresiones y Paisajes (read my review here) based on the trip in 1918. Through his success, he moved to Madrid a year later to the Residencia de Estudiantes to study at the University of Madrid.

García Lorca studied philosophy and law, but his heart lay in writing. He struck up friendships with Salvador Dalí, Luis Buñuel, Gregorio Martina Sierra and Juan Ramón Jiménez, and published his first work of poetry two years into his studies. More poetry, essays and plays followed, with his most popular poetry Romancero Gitano published in 1928. García Lorca found inspiration in the land and the people of Spain, seeing it through less-than traditional eyes, instead finding beauty in new lights. In 1927 a play opened by Salvador Dalí had García Lorca at his side, to great acclaim, after play failures five years earlier.

The mid-twenties were filled with strong collaboration between García Lorca and Dalí, though Dalí rejected García Lorca’s romantic advances. By 1928, the friendship became strained, and García’s Lorca also broke off his affair with sculpter Emilio Soriano Alarén, which enhanced García Lorca’s depression. The constant stress of being a public figure, and having to hide his true self weighed on him (same-sex relationships were technically legal between 1881- 1928, and then 1932 -1936, but in a deeply Catholic nation it wasn’t considered acceptable). He was being typecast as a gypsy poet, as gypsies were one of his predominant themes in his work. García Lorca wanted to adapt and live his art. Dalí and Luis Buñuel released a film in 1929, without García Lorca’s help, and Dalí married, leaving García Lorca feeling he was being edged out of the group and the depression only grew worse. His family shipped him to the US in 1929 to recuperate from his worries. García Lorca flirted with new styles, though his work would not be published until after his death.

García Lorca returned to Spain after a year and then in 1931 the Second Spanish Republic was born. The young writer was in charge of the Teatro Universitario La Barraca. Thanks to the new government education programme, García Lorca toured rural Spain to bring free art to the public. With little equipment and a tiny stage, the masses got to see García Lorca acting and hear his work performed. Seeing the poor populations of Spain and their reaction to their first (sometimes only ever) art performances drove García Lorca to believe art could change lives with plays about social action. The La Barraca tour created three of Garcia Lorca’s best plays – Blood Wedding, Yerma and The House of Bernarda Alba, all about standing up to the bourgeois.

After taking Blood Wedding to Argentina in 1933, García Lorca was on a roll. He returned home and created Play and Theory of the Duende, and wrote about how art needed to understand death, and reasoning limitations, and then returned to his roots of romance in his poetry (after a love affair with Juan Ramírez de Lucas) with the amazing Sonnets of Dark Love. But La Barraca had their funding cut in 1934 and closed in April 1936. García Lorca kept writing over summers at home in Huerta de San Vicente outside Granada, adding to his works with When Five Years Pass and Diván del Tamarit.

But as everyone knows, García Lorca was living in a deeply troubled world. The Spanish Civil War broke out in July 1936, and García Lorca knew his work on rebelling against the wealthy and his outspoken views on right-wing politics could see him as a target. A spokesman for the people was not going to be welcome anymore. Granada was in turmoil; not one of the cities to be initially overthrown by the rebel Nationalists, but it had martial law imposed. Bombings became frequent and the huge divide between left or right (poor or rich) was so stark that fighting emerged everywhere. García Lorca was not political, but when push came to shove, he supported those with nothing, after years of seeing deprivation in his country and abroad.

García Lorca left his home and stayed with his friend Luis Rosales in central Granada, but nowhere was safe. Lorca’s brother-in-law, Granada Mayor Manuel Fernández-Montesinos was assassinated during fighting on August 18. Hours later, fascist militia turned up at the Rosales’ residence and García Lorca was arrested, no reason given. He had been visited and interrogated weeks earlier, but when a right-wing politician came and got García Lorca alongside armed men, all of García Lorca’s fears came true.

García Lorca was held overnight by armed gunmen, their whereabouts or activities murky. The following morning, García Lorca and three others – Joaquín Arcollas Cabezas, Francisco Galadí Melgar and Dióscoro Galindo González – were driven out to Fuente Grande, the middle of nowhere between the towns of Víznar and Alfacar. After digging their own graves, García Lorca and the others were executed.

While the world was deprived of García Lorca from then on, the why’s and how’s have been debated ever since. He was shot by fascist forces, though his arrest came from CEDA, a conservative Catholic political group. Some think it was part of an elimination process of all who supported Marxism. His murderers spoke of his sexual orientation, leading that to be a theory on his killing, along with some kind of same-sex love and jealousy theory. García Lorca had friends in right and left-wing groups. He supported the left-wing government and had spoken at gatherings supporting the left. He also had communist supporters, yet was arrested in the home of a leading Falange fascist, and regularly met with Falange leader José Antonio Primo de Rivera. Francisco Franco himself ordered an investigation on the execution, but the paperwork has never been found.

Since the undignified death, countless have sought to find García Lorca’s burial place. One early search was by author Gerald Brennan himself, as documented in the wonderful The Face of Spain in 1949. Despite many attempts, García Lorca was never found in the Franco era (1939-1975). The site of the executions was identified in 1969 by a man who said he helped García Lorca dig his grave, but it wasn’t until 1999 that digging by the University of Granada could begin. Nothing was found. García Lorca’s family long denied permission for people to dig up their relative, but relatives of another man also executed continued to push for answers, which the García Lorca family agreed to. DNA samples were taken from all families and in 2009, it was time again to find García Lorca.

After two weeks’ work, samples were taken from a site for testing. No bones were found, and no bullets were uncovered. The grave was very shallow, about 40 cm deep, and could not have been a 70+ year-old grave-site. Three years later, another dig was launched, 500 metres from a first site, which also uncovered nothing. People who claimed to be part of the killings, hired men out killing for the Falange, claimed that García Lorca was a target after writing The House of Bernarda Alba, and the people portrayed in the story wanted him gone.

The Barranco de Viznar, a nearby spot of mass civil war graves in the wilderness, has been suggested as a site where García Lorca may lie, killed or moved there during the war. A memorial headstone lies there for García Lorca stating ‘We are all Lorca’. An olive tree at Fuente Grande has a memorial for García Lorca, where flowers are laid every year. All his family homes are now museums in Granada, along with a park named Parque Federico García Lorca. A famous statue of García Lorca stands in Plaza Santa Ana in Madrid, and his niece runs The Lorca Foundation in his honour.

García Lorca’s work was banned by Franco until 1953, and then censored for the rest of the Franco era. Since then more work has been published and celebrated, along with new publications from unpublished manuscripts held dear by his family. Searches and theories on his death remain ongoing 80 years later. This month, Argentinian federal judge Maria Servini has agreed to take on the García Lorca case, sequestering paperwork on the killing of the poet, while she is also prosecuting over other civil war deaths. Perhaps one day, Federico García Lorca will be found.

~~

This is not a detailed analysis, instead a simplified report of Lorca’s life and death. Feel free to suggest an addition/clarification/correction below. All photos are linked to source for credit.